Happy Lunar New Year from the USC US-China Institute!

Talking Points, Presidential Debates Edition, Sept. 27, 2016

|

|

Talking Points

Presidential Debates Edition

|

In 1960, when the first televised U.S. presidential debates took place, tensions in the Taiwan Strait and relations with China loomed large. Fifty years ago, candidates Sen. John F. Kennedy and Vice Pres. Richard M. Nixon devoted considerable time to whether the U.S. should, if necessary, assist the Kuomintang government on Taiwan in the defense of two islands close to the Chinese mainland. The names Quemoy (Kinmen 金門) and Matsu (馬祖) appeared in all four of the debates more than any single American city. It was the height of the cold war and memories of conflict on the Korean peninsula were fresh in the memories of many.

In 1960, when the first televised U.S. presidential debates took place, tensions in the Taiwan Strait and relations with China loomed large. Fifty years ago, candidates Sen. John F. Kennedy and Vice Pres. Richard M. Nixon devoted considerable time to whether the U.S. should, if necessary, assist the Kuomintang government on Taiwan in the defense of two islands close to the Chinese mainland. The names Quemoy (Kinmen 金門) and Matsu (馬祖) appeared in all four of the debates more than any single American city. It was the height of the cold war and memories of conflict on the Korean peninsula were fresh in the memories of many.China was not a significant part of most subsequent debates until 1992. In July of that year, Bill Clinton accepted the Democratic presidential nomination pledging he would not “coddle tyrants, from Baghdad to Beijing.” In Los Angeles in August, he complained that Pres. George W. Bush "sent secret emissaries to China, signaling we would do business as usual with those who murdered freedom in Tiananmen Square.'' So in the October debate, it wasn’t a surprise that the candidates were

They weren't always smiling in 1992. |

|

asked what the U.S. could do to influence China’s party-state. Clinton argued the U.S. had leverage because China had a $15 billion trade surplus with the U.S. and that the U.S. could withhold Most Favored Nation (MFN, lowest tariff rate) status. Bush argued that would risk isolating China and cause the country to turn inward. That first debate in 1992 was unique, featuring a third candidate, billionaire Ross Perot. Perot argued that time was on America’s side and that China’s elderly leaders would be replaced.

Of course, China continued to receive MFN and in 2001 entered the World Trade Organization, accelerating its rise as a manufacturing and trading powerhouse. By 2004, Bush’s son, George W. was running for re-election. In the debates with Sen. John Kerry, he mentioned his meeting at the ranch in Crawford with Chinese leader Jiang Zemin. He was counting on China’s help in curbing North Korea’s nuclear weapons ambitions. Kerry focused on the problem of disappearing jobs. He targeted the tax code which allowed companies to defer taxes on income earned and retained abroad, thus encouraging companies to produce abroad. And he complained that the Chinese government kept the value of its currency artificially low to boost exports.

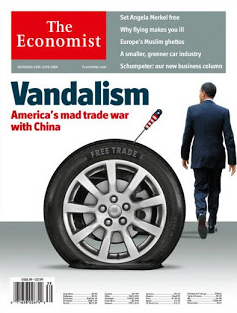

In 2008 and 2012, Republican candidates Sen. John McCain and former Gov. Mitt Romney focused on federal spending which caused America to borrow money from China. Senator and then President Obama focused on the need to invest in education and green technology in order to stay competitive with China. Obama argued that developing energy resources in the U.S. would allow America to avoid borrowing from China in order to buy oil from Saudi Arabia. The time devoted to China in 2012 was particularly extensive. Romney wanted to do away with Obamacare and federal support for PBS so the U.S. wouldn’t have to borrow from China. Obama rejected Romney’s contention that he would get tough on China, saying Romney “invested in companies that were pioneers of outsourcing to China.” Obama took credit for putting a high tariff on tire imports from China, preserving 1,000 jobs and he complained that Romney wanted to preserve tax breaks for companies that invested abroad rather than creating jobs at home.

|

| The Economist wasn't a fan of Obama's imposition of tariffs on Chinese tires. |

Romney responded by essentially arguing that since the U.S. and Chinese economies are so linked, that all Americans, the President included, invested in China, through their retirement accounts or pension funds. Even so, Romney frequently repeated his pledge that he would declare China a currency manipulator on “day one,” and impose tariffs as necessary.

Which brings us to last night and the highly anticipated first debate between former Sec. of State Hillary Clinton and billionaire businessman Donald Trump. The summary above includes many issues that were revisited by this year’s leading candidates. Strung awkwardly across several questions and answers, Trump complained that American taxes and regulations, combined with Chinese currency manipulation and other unfair practices made possible by inept U.S. officials combined to cost the U.S. jobs. What makes the situation so much worse, he said, is that America’s “third world” infrastructure will be difficult to rebuild given the size of the national debt. Trump put the blame for all this on Obama and Clinton. The former secretary of state argued that during her time in office, exports to China and the rest of the world rose dramatically. She argued that requiring the wealthy to pay their fair share of taxes (reminding Trump that many are curious about what taxes he pays and who he borrows from) would provide resources that could be invested in education and infrastructure, creating jobs at home and making the U.S. more competitive abroad. She further noted that bringing China into help pressure Iran into halting its nuclear weapons program was difficult but necessary and effective. On weapons proliferation, Trump argued China had total power over North Korea and should go in and end that country’s weapons development. Two more debates lie ahead.

What a review of U.S. presidential debate transcripts reveals is both continuity and change in U.S.-China relations and in American perceptions of our ability to influence Chinese policy. We see some issues such as enforcement of trade agreements as a constant – once trade becomes significant. Before that, the cold war provided the overriding context. And rarely do candidates acknowledge the limits of American power, be it hard in the form of military capacity or market size, or soft in the form of values and culture. One of the most evident trends, however, is the way in which the U.S. and China are increasingly intertwined. Almost any topic raised in a debate today can easily turn to China from cybersecurity and cultural industries to innovation and inequality.

So there are “China cards” to collect and to play. We hope you’ll join us at USC on Thursday. At our “The China Card” conference, we will be talking about China in American politics and China policy options for the next administration. The conference marks the USC U.S.-China Institute’s 10th anniversary. We hope you’ll attend or at least wish us well via email, Facebook or Twitter (use the #TheChinaCard hashtag, of course!). Of course, we would love to receive an anniversary gift. You can send one via our support page.

The China Card: Politics vs. Policy

8:45 am - 6 pm

September 29, 2016

|

|

If you’d like to explore China in American presidential debates, we’ve culled the transcripts for you. Our 39 page compilation is available here. Please help us by sharing Talking Points with others and encouraging them to subscribe. We have other election related materials at our website:

USCI has monitored China in American politics for years. In addition to the debate transcript excerpts, please take a look at:

Election ’08 and the Challenge of China (or watch it on YouTube)

2010: China in US Campaign Ads and Election Outcomes

2012: China in US Campaign Ads

Best wishes,

Keep us out of your spam/promotion folder - add uschina@usc.edu to your address book.

Featured Articles

We note the passing of many prominent individuals who played some role in U.S.-China affairs, whether in politics, economics or in helping people in one place understand the other.

Events

Ying Zhu looks at new developments for Chinese and global streaming services.

David Zweig examines China's talent recruitment efforts, particularly towards those scientists and engineers who left China for further study. U.S. universities, labs and companies have long brought in talent from China. Are such people still welcome?