Happy Lunar New Year from the USC US-China Institute!

Chou, Mount Wutai: Visions of a Sacred Buddhist Mountain, 2018

Wen-shing Chou's study of Mount Wutai was reviewed by Yong Cho for the History of Buddhism discussion list and is republished here by Creative Commons license.

September 29, 2021

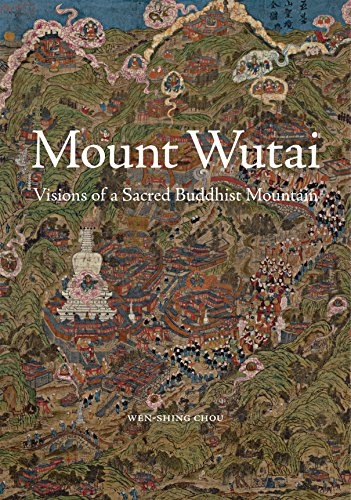

Wen-Shing Chou. Mount Wutai: Visions of a Sacred Buddhist Mountain. Princeton Princeton University Press, 2018. 240 pp.,ISBN 978-0-691-19112-6.

Review by Yong Cho, September 29, 2021

Mount Wutai, a sprawling area that is framed by a cluster of five plateaued summits in northern China, has been an important site of Buddhist devotion in East and North Asia since at least the fifth century CE. Buddhists understood--and continue to understand--Mount Wutai as an earthly abode of Mañjuśrī, the bodhisattva of wisdom. Because of this, various ruling houses throughout history that controlled the area were important patrons of Buddhist art and architecture on and around the mountain. This was particularly true during the Qing period (1644-1911), when its Manchu rulers fashioned themselves as the living incarnations of Mañjuśrī.

Mount Wutai, a sprawling area that is framed by a cluster of five plateaued summits in northern China, has been an important site of Buddhist devotion in East and North Asia since at least the fifth century CE. Buddhists understood--and continue to understand--Mount Wutai as an earthly abode of Mañjuśrī, the bodhisattva of wisdom. Because of this, various ruling houses throughout history that controlled the area were important patrons of Buddhist art and architecture on and around the mountain. This was particularly true during the Qing period (1644-1911), when its Manchu rulers fashioned themselves as the living incarnations of Mañjuśrī. In this erudite book, Wen-shing Chou tells the story of how Mount Wutai became a dynamic site of political, religious, and cross-cultural negotiations during the Qing, not only for the members of the imperial family and the imperially sponsored Géluk Buddhist monastics, but also for the pilgrims traveling to the mountain from different corners of Buddhist Inner Asia. As the author notes, several important publications that focus on Mount Wutai have appeared in recent years. This book, however, is unique because it transcends the disciplinary boundaries that often separate the scholars of Chinese, Tibetan, Manchu, and Mongolian Buddhist art and history. The author is able to achieve this because of her superb ability to engage with a dazzling array of primary sources written in both Tibetan and Chinese, as well as her analytical skills through which she brings together a diverse body of visual and material evidence into conversation.

The book argues that there was no singular, monolithic vision of Mount Wutai during the Qing period. Rather, the meaning of the mountain was multifaceted and contingent on the specific cultural, linguistic, and sociopolitical identity of the historical actor who was experiencing the mountain. Just as different groups of people used various names to refer to Mount Wutai (for example, as the author notes [p. 3-4], "Wutai Shan," "Qingliang Shan" or "Zifu" in Chinese, "Riwo Tsenga" or "Riwo Dangsil" in Tibetan, "Serüün Tunggalag Agula" or "Utai Shan" in Mongolian), there were multiple pathways and routes through which one could explore and interpret Mañjuśrī's earthly abode. In order to capture this panoramic view of the mountain, Chou structures her monograph as a series of intersecting case studies on different visual and literary productions that the mountain inspired. Each of these case studies represents the "diverse yet mutually inclusive views" (p. 10) of the mountain.

A reader might expect that a book titled _Mount Wutai_ would be solely devoted to the art and architecture that constitute the physical environment of the mountain proper. This book, however, explores a far richer set of associations than what the title implies. Of course, all of the works that Chou presents in the book are deeply connected to Mount Wutai. Each of them, however, was produced and circulated in different contexts within the Qing Buddhist world, often far away from the mountain itself.

For example, Chou begins the book during the period of the emperor Qianlong's reign (r. 1735-96) with a discussion of temples and Mañjuśrī icons produced in Beijing and Chengde based on the original models located in Mount Wutai (chapter 1). Chou then shifts gears to study a Tibetan-language Mount Wutai guidebook, which she discovered was a translation of an older Chinese gazetteer of the mountain (chapter 2). Qianlong's religious teacher Rölpé Dorjé

(1717-86) began writing this guidebook, but it was completed posthumously by his disciples in 1831. Chou also investigates biographical writings and lineage paintings of religious luminaries within the Qing-Géluk order in order to highlight the central role that Mount Wutai played within the visual and literary conflations of Rölpé Dorjé, Qianlong, and Mañjuśrī (chapter 3). Chou even examines cartographic representations of Mount Wutai (chapter 4). She focuses on two different types of maps. The first is a wall painting in an Inner Mongolian monastery of Badgar Choiling Süme dated to the early 1800s, and the second is a set of woodcut prints, originally carved by a Khalkha Mongol monk, Lhundrub, at Mount Wutai's Cifu Temple in 1846 but hand-colored afterwards by different artists.

Throughout the book, Chou employs the theoretical framework of "translation" to provide a nuanced reading of various visual and literary productions inspired by Mount Wutai. First and foremost, what is crucial for the author is the transformative potential that is inherent in the act of translating. In a translated work, the meanings of the original can be inflected or changed depending on the needs of the translator. For example, Chou interprets the Mañjuśrī paintings by the Qing court artist Ding Guanpeng (1708-71) as examples of visual translation in service of the Qing rulership (chapter 1). Even though Ding's paintings were supposedly replicas of a model in Mount Wutai, they were not faithful copies. As Chou points out, in one of them, Ding rendered Mañjuśrī's face to bear a resemblance to Qianlong himself. Here, Chou perceptively makes a case that this was an act of a visual translation that allowed Ding's painting to reinforce Qianlong's identity as a Mañjuśrī-incarnate and thereby enact his universal kingship. Rölpé Dorjé and his disciples' Tibetan translation of the Chinese gazetteer of Mount Wutai, too, is understood as an act of revisionism (chapter 2). By analyzing how the Tibetan monks abridged and reframed the original Chinese text, Chou convincingly demonstrates how this act of selective translation could fulfill the Géluk sectarian ambition to incorporate their own genealogies into the history and geography of China. It allowed the Géluk monks to place themselves at the center of the Pan-Buddhist cosmography.

The framework of translation also allows Chou to capture Qing Mount Wutai as an open space of flexible cultural and linguistic identities, where the Buddhists of Inner Asian, Chinese, and Manchu origins could productively engage with one another. As represented by the quadrilingual inscriptions in Tibetan, Mongolian, Manchu, and Chinese that accompany the lineage albums of Qianlong and Rölpé Dorjé (chapter 3), the fluid translation across cultures and languages was one of the defining features of Mount Wutai's visual and material worlds. Whether as a mural or a printed (and then colored) map, the cartographic representations of Mount Wutai, too, materialized as an entanglement of multiple topographical and pictorial practices associated with Chinese, Tibetan, Mongolian, and Manchu-imperial visual cultures (chapter 4). These flexible multilingual maps, in turn, could become an effective visual tool that mediated the experience of Mount Wutai for those who wished to encounter the mountain, either through an actual pilgrimage or veneration as an icon.

Some of the most exciting moments in the book are when the author conducts art-historical detective work by thinking with visual data. The section where Chou envisions the colorers of the Cifu Temple prints as "viewers" of the map is particularly illuminating (pp. 155-64). She creatively interprets the patterns of coloring as the "visible traces" of how the colorers comprehended Mount Wutai. Comparing two very differently colored Cifu Temple maps now kept in the Museum of Cultures in Helsinki and the Rubin Museum of Art in New York, Chou brilliantly concludes that the Helsinki version was most likely colored at or near Mount Wutai by a Chinese or a Mongol colorer who did not read Tibetan. This map was most likely intended for use by Mongol pilgrims. On the other hand, the Rubin version, according to Chou's analysis, was most likely painted by someone far away from Mount Wutai, interpreting the iconography of the printed map by reading the Tibetan inscriptions. The silk-brocade mounting of the Rubin map suggests that it was used as an icon of veneration to Mount Wutai, rather than as an actual map used during the pilgrimage. In a book that is largely concerned with the intersections between the visual or literary production on Mount Wutai and the Qing-Géluk politics of sacred geography, these exciting moments of Chou's art-historical prowess provide a breath of fresh air. It reminds the reader of the multidimensionality of visual arts beyond the realm of imperial and monastic politics.

_Mount Wutai_ is deeply researched, theoretically sophisticated, and brilliantly conceptualized. Its production quality is also lavish with color illustrations that bring to life Chou's nuanced and complex arguments. The engaging stories and intriguing images that fill the pages of this book make it appropriate for classroom use. At the same time, the meticulously reconstructed case studies that bring into conversation various Tibetan and Chinese primary sources with a diverse group of visual and material objects make it an invaluable resource for specialist readers in art history and Buddhist studies. This impressive monograph opens up a new framework and methodology for scholars of transcultural Buddhism and Buddhist art. It is a must-read for anyone interested in Tibetan, Mongolian, Chinese, and Manchu cultures, religion, and sacred geography.

Featured Articles

January 4, 2024

We note the passing of many prominent individuals who played some role in U.S.-China affairs, whether in politics, economics or in helping people in one place understand the other.

Events

Thursday, March 21, 2024 - 4:00pm PST

Ying Zhu looks at new developments for Chinese and global streaming services.

Tuesday, March 19, 2024 - 4:00pm

David Zweig examines China's talent recruitment efforts, particularly towards those scientists and engineers who left China for further study. U.S. universities, labs and companies have long brought in talent from China. Are such people still welcome?