Happy Lunar New Year from the USC US-China Institute!

Gardens, Art, and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints

“Gardens, Art, and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints” explores the art of pictorial prints from the late 16th century to the 19th century—and marks the first time the public can see The Huntington’s rare Ten Bamboo Studio Manual.

Where

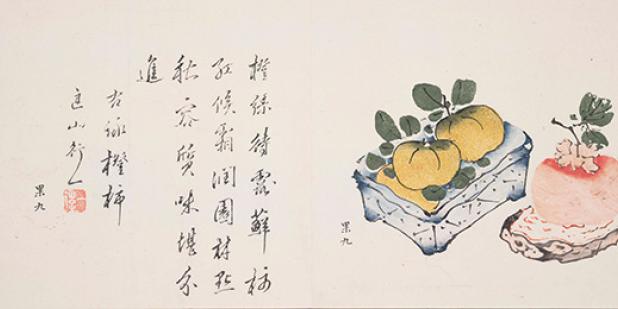

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens will present a major international loan exhibition exploring the art, craft, and cultural significance of Chinese woodblock prints made during their golden age, with works made from the late 16th century through the 19th century. “Gardens, Art, and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints” (Sept. 17, 2016 – Jan. 9, 2017) brings together 48 of the finest examples gathered from the National Library of China, Beijing; the Nanjing Library; the Shanghai Museum; and 14 institutional and private collections in the United States. The exhibition presents monumental visual accounts of sprawling, architecturally elaborate “scholar’s gardens,” alongside delicate prints with painterly textures and subtle colors depicting plants, birds, and other garden elements so finely wrought they might be mistaken for watercolors. A highlight of the exhibition is The Huntington’s rare edition of the Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Painting (ca. 1633–1703), acquired in 2014, and on public view for the first time in this exhibition.

Research informing the exhibition and an accompanying catalog reveals much about the history and significance of Chinese pictorial printing during the period, including its influence on better-known Japanese woodblock artists and collectors. Coveted for their artistic merit and technical virtuosity, Chinese illustrated books and pictorial works were collected by the literati and wealthy merchant classes in both China and Japan. The Ten Bamboo Studio Manual, for example, contains the inscriptions of five renowned Japanese artists, successive owners who treasured the artistically ambitious and visually creative volumes as an important resource.

The founding curator of The Huntington’s Chinese Garden, June Li, is co-curator of the exhibition and co-author of the catalog, along with Chinese woodblock print specialist Suzanne Wright, associate professor of art history at the University of Tennessee.

“Gardens, Art, and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints” unites several interests at The Huntington. It is the home of one of the most extensive collections of early printed books in the nation, various collections of prints by European and American artists, and one of the largest Chinese scholar’s gardens outside of China.

“This exhibition is utterly evocative of The Huntington's transdisciplinary nature,” said Laura Skandera Trombley, Huntington president. “Woodblock prints were formative communication and aesthetic tools that served a number of purposes over time, from disseminating Buddhist teachings to depicting ideals of beauty. This perfect fusion of art and language, an integration of emotion and intellectual pursuit, is evidenced in The Huntington’s art and library collections, and is embodied in our stunning Suzhou-style Chinese Garden. We are enormously grateful for June Li’s commitment and guiding vision for this extraordinary exhibition.”

During the late Ming (1368–1644) and early Qing (1644–1912) dynasties, an increase in wealth, stemming in part from the salt, rice, and silk industries, led to higher levels of literacy and education. Consumer demand for printed words and images increased as merchants and scholars looked for ways to display their taste in drama, poetry, literature, and art. For these elites, gardens were central to a cultured life, appearing frequently in woodblock prints as subject or setting. By the 1590s, several enterprising publishers were successfully meeting the strong demand for woodblock prints. They hired renowned designers, carvers, and printers to produce sophisticated and exquisite works, raising the standards of printmaking. During the last decades of the Ming dynasty, several centers of printing around the lower Yangzi River delta grew in reputation, ushering in a golden age of Chinese pictorial printing.

“In the realm of Chinese art, pictorial woodblock prints are not as familiar as paintings, calligraphy, or ceramics,” said Li. “The subject of woodblock prints usually brings to mind Buddhist icons, Daoist deities, or folk images, rather than refined and artistic works. But, over the past few years, scholars researching the historical and artistic aspects of these prints have re-introduced a trove of beautiful works that are highly accomplished.”

Building on this story, “Gardens, Art, and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints” is organized into thematic sections with explanatory panels in both English and Chinese.

Exhibition Flow

In the first gallery of “Gardens, Art, and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints,” visitors will find an impressive nine-and-an-half-foot long hand scroll that was commissioned by the Song emperor Taizong (r. 976–97). An unusual Buddhist work that depicts landscape rather than images of deities, it is the earliest and only religious work in the exhibition, showing the lofty achievements of woodblock printers by the 10th century, with enormous clarity of line and painstaking attention to the details of mountains, streams, trees, and tiny figures.

The accomplishments of such early printing established the technical foundation from which later Ming and Qing artists grew. Illustrations of the Garden Scenery of the Hall of Encircling Jade, an extraordinary set of 45 prints produced around 1602 to 1605 will be displayed in facsimile (the only evidence that remains of the original). Taken as a whole, the prints illustrate the enormous garden estate of a successful merchant, scholar, and book publisher of the early 17th century. The detailed prints show what seems to be acres of a fashionable garden, with a large, elegant hall framing scholars seated in conversation; a courtyard where figures re-enact a famous poetry game around a table; an enclosure for carefully sculpted penjing (bonsai trees); and more than a hundred names inscribed on buildings, ponds, and rocks. The print has an elevated viewpoint and changing perspectives that allow glimpses into interior spaces, revealing a cultivated life of books and men in scholars’ robes deep in discussion.

The exhibition next focuses exclusively on prints about gardens, both historical and fictional. Historical gardens include famous sites recorded by emperors, such as Suzhou’s Lion Grove, a popular tourist destination to this day. Another imperial work, a scroll more than 25 feet long (six feet of which will be displayed), shows urban gardens and the bustle of daily life in 18th century Beijing.

The effects of exchanges between European missionaries and the Chinese also are explored in the exhibition. One publisher incorporated biblical illustrations into his ink catalog, produced around 1616. The Qianlong emperor in 1783–86 commissioned a set of large copperplate engravings in a European style that showed details of the European pavilions in his private retreat.

Another section of the exhibition explores the styles of print artists from the late 16th through the 18th centuries in publishing centers such as Hangzhou, Huizhou, Wuxi, and Suzhou. On view are several examples by different publishers illustrating a single popular story, the Story of the Western Chamber, making clear their varying visual and artistic interpretations. In some cases, prints were made to resemble known paintings. Sometimes famous painters, such as Chen Hongshou (1598-1652), designed works expressly for printing. The exhibition includes a rare early edition of Chen’s version of the Story of the Western Chamber, as well as a set of cards he designed for a drinking game.

The exhibition also looks at accomplishments in multi-color and embossed printing, such as beautifully printed guides offering suggestions for cultivating taste. These manuals prescribed appropriate pastimes for a cultivated life, instructed on calligraphy, and advised on chess strategy and drinking games for men, and embroidery patterns for women. They also illustrated musical and dramatic works such as the popular Peony Pavilion. Many of these leisure activities took place in the garden, and prints showing scholar’s rocks, which had become precious items for the discerning collector, will be represented by finely printed editions of well-known works including a rare edition of The Stone Compendium of Plain Garden. Two examples of actual scholar’s rocks from The Huntington’s collection will be on view to complement the book.

Additionally, four iPads in the galleries will allow for a deeper investigation of Illustrations of the Garden Scenery of the Hall of Encircling Jade (a work showing the large garden estate of the successful merchant and publisher Wang Tingna), and allow visitors to see all the leaves of The Huntington’s Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Painting, a work that due to its delicate nature can only be viewed a few leaves at a time in the galleries.

Education Gallery: Printing Techniques

Visitors of all ages can view Chinese woodblock printing techniques in a gallery featuring a replica of a printing table, along with carving tools, colored inks, paper, brushes, and burnishers. To better understand the multi-color printing process, a set of woodblocks and step-by-step prints replicating a page of the Ten Bamboo Studio Manual will be on view, a display commissioned from the Shanghai publisher Duo Yun Xuan especially for the exhibition.

Support for this exhibition was provided by the Henry Luce Foundation and the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation. Additional funding was provided by Richard A. Simms and the Ahmanson Foundation Exhibition and Education Endowment.

Exhibition Catalog

“Gardens, Art, and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints” is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalog of the same name featuring contributions by co-curators T. June Li and Suzanne E. Wright. Li details the origins and provenance of The Huntington’s Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Painting, a landmark of multi-block color printing, with particular emphasis on its appeal to 18th- and 19th-century Japanese collectors. Wright traces the development of three distinct regional styles of woodblock-printed illustrations during the late Ming dynasty, with striking examples of each style drawn from the exhibition. The 176-page volume, published by The Huntington, features more than 150 illustrations, including full-color plates of each work in the exhibition.

The catalog is made possible by a generous donation from the Sammy Yukuan Lee Family.

Gardens, Art, and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints

by T. June Li and Suzanne E. Wright

September 2016

176 pages

153 color illustrations, 2 maps

ISBN 978-0-87328-267-3

Cloth, $49.95

Published by The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Available at thehuntingtonstore.org

Related Events

Is a Picture Worth a Thousand Words? Chinese Woodblock Prints of the Late Ming and Qing Periods

October 3, 2016

7:30 pm

Free lecture, Rothenberg Hall

“How Can I Disdain…this Carving of Insects?” Painters, Carvers, and Style in Chinese Woodblock Printed Images

October 25, 2016

7:30 pm

Free lecture, Rothenberg Hall

The Huang Family of Block Cutters: The Thread that Binds Late Ming Pictorial Woodblock Printmaking

November 22, 2016

7:30 pm

Free lecture, Rothenberg Hall

Word and Image: Chinese Woodblock Prints,

November 12, 2016

8:30 am – 5:00 pm

Symposium, Rothenberg Hall

View schedule

Chinese Color Woodblock Printing

November 20, 2016

Workshop

See Huntington Calendar for details

Featured Articles

We note the passing of many prominent individuals who played some role in U.S.-China affairs, whether in politics, economics or in helping people in one place understand the other.

Events

Ying Zhu looks at new developments for Chinese and global streaming services.

David Zweig examines China's talent recruitment efforts, particularly towards those scientists and engineers who left China for further study. U.S. universities, labs and companies have long brought in talent from China. Are such people still welcome?