Happy Lunar New Year from the USC US-China Institute!

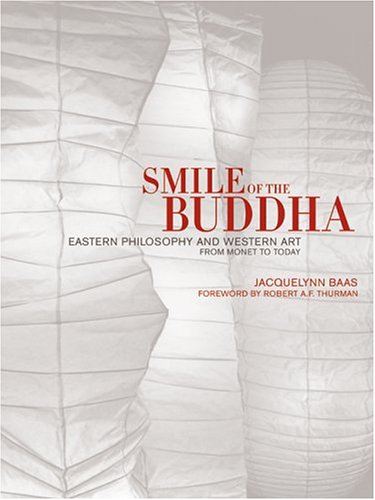

Baas, Smile of the Buddha: Eastern Philosophy and Western Art from Monet to Today, 2005.

.

Published by: H-Buddhism (February, 2007)

Jacquelynn Baas' latest book, Smile of the Buddha represents the growing interest in religion and spirituality in contemporary visual art. As in  other areas of society since the French Revolution, religion and its arts were considered anathema by the spirit of progress and it was thought that they were no longer relevant to contemporary artists. But in recent years art historians, led by those holding an interest in Zen Buddhism, are re-examining modern art from the view point of religion. Recently we have witnessed the publication of James Elkins'On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art (2003), Eleanor Heartney's Postmodern Heretics: The Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art (2004), and Jacquelynn Baas' previous book, Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art(2004). Zen Buddhism is not new to the contemporary art scene, as it affected the work of the Beat poets, such as Alan Ginsberg (1926-1997) and New York artists John Cage (1912-1992) and Robert Rauschenberg (b. 1925) under the tutelage of D.T. Suzuki (1870-1967) at Columbia University just after World War II. In these times when technology is art and god all at once, can religion or spirituality co-exist with modern art?

other areas of society since the French Revolution, religion and its arts were considered anathema by the spirit of progress and it was thought that they were no longer relevant to contemporary artists. But in recent years art historians, led by those holding an interest in Zen Buddhism, are re-examining modern art from the view point of religion. Recently we have witnessed the publication of James Elkins'On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art (2003), Eleanor Heartney's Postmodern Heretics: The Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art (2004), and Jacquelynn Baas' previous book, Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art(2004). Zen Buddhism is not new to the contemporary art scene, as it affected the work of the Beat poets, such as Alan Ginsberg (1926-1997) and New York artists John Cage (1912-1992) and Robert Rauschenberg (b. 1925) under the tutelage of D.T. Suzuki (1870-1967) at Columbia University just after World War II. In these times when technology is art and god all at once, can religion or spirituality co-exist with modern art?

To appreciate Baas' book, one should possess some degree of awareness of the work of such writers as Stephen Batchelor regarding the state of Buddhism in the West. The intent of the book is "to provide a new lens through which to perceive and interpret the art of the recent past" by way of a survey of selected artists (p. 1). Some of these artists openly profess belief in Buddhism, but most do not. Baas' criteria for Buddhist art is the possibility of an artist's contact with Buddhism and Asia in creating a certain style or genre of art. The nature of the art may not be obvious, as she states, "Buddhism's influence is implicit rather than explicit." (p. 10).

Baas begins her survey by going back over a hundred years to Claude Monet (1840-1926) and asserts that his works documenting fleeting light were influenced by Buddhist thought concerning evanescence--a somewhat specious claim. Baas cites the influence of Japanese Ukiyoe prints on Monet's art and a change in philosophy brought on by world events and the translation of Buddhist books in the 1870s by Max Muller and others (p. 21-22). But despite the fact that the art is described as resonating with Buddhist philosophy, there is no way of knowing whether Monet actually owned or read any of the books cited by Baas. The thesis is fascinating, but this reader is unconvinced. Her studies of other artists, such as Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) and Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), are equally facile, as there has been no presentation at all of any information existing on the topic. The chapters about Odilon Redon (1840-1916) and Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), who were clearly spiritual artists (with the former possibly meriting characterization as Buddhist artist), are altogether far too short. In total Baas discusses the work and philosophy of twenty artists, causing her work to read more like an art catalogue than a scholarly monograph. The strong point of the work is its emphasis of the importance of the effects of belief on art. The book also provides a much needed overview of the historical period. While the taste of information provided regarding a wide range of artists is helpful, one desires to know more. Nonetheless, at this point in time, without doubt Baas' work is important as an introduction to a topic that will certainly draw more attention in the future.

To someone who works mainly in the area of the history of traditional Japanese Buddhist art, much of the work illustrated in Baas' book seems secular and appears to have little to do with religion or spirituality of any sort. The work that is discussed ranges from Impressionism to Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art to field painting and the performance art of Laurie Anderson. This is an exhaustive range for such a short book. One needs to keep in mind that the works that she cites are not Buddhist art but Buddhist-influenced art; therein lies the difference.

Baas believes that Duchamp's first "readymade" piece, Bicycle Wheel (1913), was inspired by Indian images of the Dharma Wheel that he saw at the Ethnographic Museum in Berlin and the Musée Guimet in Paris, which he described as an "object of meditation," not a work of art (pp. 86-87). Furthermore, Duchamp's act of cross-dressing as his alter-ego, Rose Sélavy, may have been influenced by the male-female sexual transformations of Guanyin in China (pp. 90-91). As well, he claimed that he had thirty-three ideas for thirty-three works, which Baas believes was influenced by twenty-fifth chapter of the Lotus Sūtra, in which the thirty-three manifestations of Guanyin are discussed (p. 90). In a later chapter concerning the musician-artist Cage, who was influenced by Duchamp, Baas cites a passage by Cage in which he reports that the master of conceptualism denied any influences from Asian philosophy (p. 173).

In a normal scholarly work one would say that Baas has contradicted herself, but in dealing with artists who make claims and counter-claims about their art, this is not so simple, as artists frequently contradict themselves. Also, modern artists find inspiration everywhere; some of the inspiration is conscious, other times it is not. I know an artist who was quite taken by A. Mookerjee and M. Khanna's book, The Tantric Way (1977). She borrowed my copy for a long time, then bought her own. She now claims that her work is influenced by Tantric art, although she has never read anything about Tantrism, only looked at illustrations. This is an example of a Buddhist-inspired artist, similar to many of those described by Baas, although she is not a Buddhist artist. With my friend there is no mention of deep faith, or even simple understanding of a philosophy, just cross-cultural appropriation of a quixotic type, which differs remarkably from the traditional Buddhist artist trained in Asia. All this, however, makes one wonder if the creator of Friar Bala's Bodhisattva (first/second century C.E.) had a touch of artistic inspiration of the same type that afflicts the modern artist?

Baas' discussion of more recent artists who can be readily linked to Dharma study groups and particular teachers of Buddhism--such as Cage, Ad Reinhart (1913-1967), Agnes Martin (1912-2004), and Robert Irwin (b. 1928)--is cogent. With the exception of Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Kandinsky, Cage, Nam Jun Paik (1932-2006) and Martin, many of the artists discussed by Baas are not usually associated with spiritual or Buddhist thought, so her selection is extremely interesting. Baas has also omitted some of the better-known spiritual artists, such as Mark Tobey (1890-1976), who was a Baha'i believer although he studied in a Zen temple, and Bill Viola (b. 1951) and Ann Hamilton (b. 1956), who are more contemporary. It would be more useful in fulfilling her desire to expound on modern Buddhist art if Baas could write a lengthy monograph about one or two of the artists that she has presented, such as Redon, who was a serious student of Buddhism and meditation, as well as an important early twentieth-century artist. As well, she needs to deal with some of the deeper questions of what defines a Buddhist believer and artist.

While Baas' book has problems, it raises many interesting questions. How do we define one who proclaims to be making Buddhist art or Buddhist-inspired art, and how do we question the nature of belief and inspiration? Well known is the fact that many of the Japanese makers of Zen paintings did so under the patronage of their warrior masters, but they themselves were followers of Amida or professed Nichiren leanings. So are the works of my friend the Tantra-inspired artist any less sincere than theirs?

At a time when the influence of Buddhism is eroding in Asia, but growing in the West, one wonders how Buddhist art will continue and what new types of genres, styles and iconographies will develop. At one time Buddhist art was considered to be dead, a relic of Asia's past, but if there continue to be Buddhists, Buddhist art will also continue, although it will be radically different from anything created before. As one who studies traditions of art-making, I recommend Baas' book as an important contribution to the field of modern Buddhist-inspired art. It will open the eyes of traditionalists and cause them to re-think the nature of Buddhist art.

Citation: Gail Chin. "Review of Jacquelynn Baas, Smile of the Buddha: Eastern Philosophy and Western Art from Monet to Today," H-Buddhism, H-Net Reviews, February, 2007. URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.cgi?path=212471173981682.

Republished with permission from H-Net Reviews.

Featured Articles

We note the passing of many prominent individuals who played some role in U.S.-China affairs, whether in politics, economics or in helping people in one place understand the other.

Events

Ying Zhu looks at new developments for Chinese and global streaming services.

David Zweig examines China's talent recruitment efforts, particularly towards those scientists and engineers who left China for further study. U.S. universities, labs and companies have long brought in talent from China. Are such people still welcome?